As the 2018 Hirshon Director-in-Residence, Sean Baker was honored for his socially engaged and stylistically brave approach to filmmaking—hallmarks of a School of Media Studies education.

“Sean’s films resonate with our students and the type of filmmaking we foster at the School of Media Studies,” says Vladan Nikolic, the newly minted dean of the school. “While Sean has recently received well-deserved mainstream acclaim, he has been active for two decades, exploring themes and characters we rarely see as a society, including the ‘hidden homeless’ in The Florida Project and transgender protagonists in Tangerine. He proves that you can make strong films with a unique vision without big budgets about people on the margins of society.”

Cruising along Highway 192 in Central Florida, Sean Baker came upon the Magic Castle, a seedy, bright-pink motel in the outer orbit of Orlando’s Walt Disney World Resort. It was the perfect setting for his next film. The Florida Project, as it would later be titled, would explore the “hidden homeless”—people living hand-to-mouth in cheap motels after losing jobs and homes in the Great Recession.

However, a few days into filming, Baker hit a 100-decibel snag. A company selling helicopter rides set up shop right across the street from their location, wreaking havoc with deafening noise at all hours of the day.

“At first, it was a nightmare. The helicopters were taking off every ten minutes,” Baker told a class of students from the School of Media Studies recently. “We didn’t know if we could use the Magic Castle or not.”

Rather than change locations, Baker made a creative decision that follows from his documentary approach to narrative fiction filmmaking: He went with it.

“I can’t imagine the film without them now,” he said of the helicopters, which he incorporated as motifs in The Florida Project. “They’re a presence throughout the film, including the ending sequence, where they play a crucial role. It was a gift in disguise.”

Embracing “happy accidents” was one of the many pieces of advice the former New School student shared with School of Media Studies students in a master class, Finding Your Film.

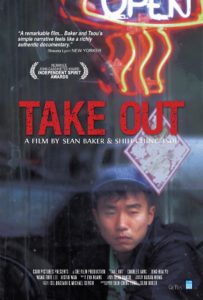

In addition to leading two master classes, Baker hosted a public screening of clips from his films, including, most recently, The Florida Project, which won or was nominated for several awards during the 2017 award season; Tangerine, which follows a day in the life of two trans sex workers in Los Angeles; Starlet, which tells the story of a young woman who finds a fortune stashed in a yard-sale thermos; Prince of Broadway, the tale of a New York street hustler who meets the son he never knew he had; and Take Out, a film about undocumented Chinese immigrant workers in New York City, written and directed by Baker and Shih-Ching Tsou, MA Media Studies ’10.

Baker is no stranger to The New School, having enrolled in editing classes at the university in 2000. It’s also where he met Tsou, who has been Baker’s production partner and artistic collaborator ever since.

“It’s amazing to see how far The New School has come; it was always a prestigious place to study, but now, 15 to 20 years later, everyone talks about it as a real destination,” says Baker, who, as a student, checked out filmmaking equipment to fellow students from the former School of Media Studies location at 55 West 13th Street.

While students gathered at the master class were eager to hear Baker’s advice, he questioned whether he was qualified to give it. The reason: To a large extent, he makes up his films as he goes along.

“It’s interesting to be in this position, because, generally, I don’t like giving advice—everyone has their own journey,” Baker said in an interview. “What I usually tell students is they’re about to set out on this journey, and it will be very unique and different from that of every other filmmaker. There’s no set formula.”

For Take Out, Baker assembled an ensemble cast of both professional and nonprofessional actors and shot without a full crew in an actual takeout restaurant during operating hours. The approach was liberating, allowing the filmmakers to focus exclusively on the acting and the story, and creating opportunities for “serendipity, happy accidents, and things we never could have expected,” Baker recalled.

“We learned a lot of lessons both on making a low-budget film and finding our film along the way,” he added. “We weren’t making it up, exactly, but we didn’t try to pre-visualize too much either.”

Tangerine evolved in a similar way. What began as a “log line” and a desire to shoot in a specific location—the intersection of North Highland Ave and Santa Monica Boulevard, the epicenter of Los Angeles’ red-light district for trans sex workers—became a 100-page screenplay. To realize the film, Baker eschewed enforcing a predetermined plot; instead, he listened to “voices of the community,” collaborating with locals who wanted to share their stories. One such story came from Kitana “Kiki” Rodriguez, who went on to become a co-star of the film.

Tangerine evolved in a similar way. What began as a “log line” and a desire to shoot in a specific location—the intersection of North Highland Ave and Santa Monica Boulevard, the epicenter of Los Angeles’ red-light district for trans sex workers—became a 100-page screenplay. To realize the film, Baker eschewed enforcing a predetermined plot; instead, he listened to “voices of the community,” collaborating with locals who wanted to share their stories. One such story came from Kitana “Kiki” Rodriguez, who went on to become a co-star of the film.

“We were at a local Jack in the Box with Kiki when she told us she suspected her boyfriend of cheating on her,” Baker recalled. “She later found out that wasn’t the case. But the next time we met her, I said, ‘You know, I think there’s something there. If that turned out to be true, what would you have done?’ She told us she would have gone and found her at the brothel down the street. And then this fictionalized journey sprang from that.”

Baker encouraged students to embrace elements like the helicopters in The Florida Project, the bustling Chinese restaurant in Take Out, and Kiki’s story in Tangerine for what they are: gifts.

Said Baker, “That stuff is exciting—it’s allowing the real life and the real world to help you write your film.”